Mogadishu, Somalia 2011-2014

“Diane Davis, Stephen Graham, Jo Beall, Mitchell Sipus, Saskia Sassen, and Mike Davis, among many others, have added immensely to our understanding of development and conflict in connected cities.”

- David Kilcullen, Out of the Mountains 2013

Background

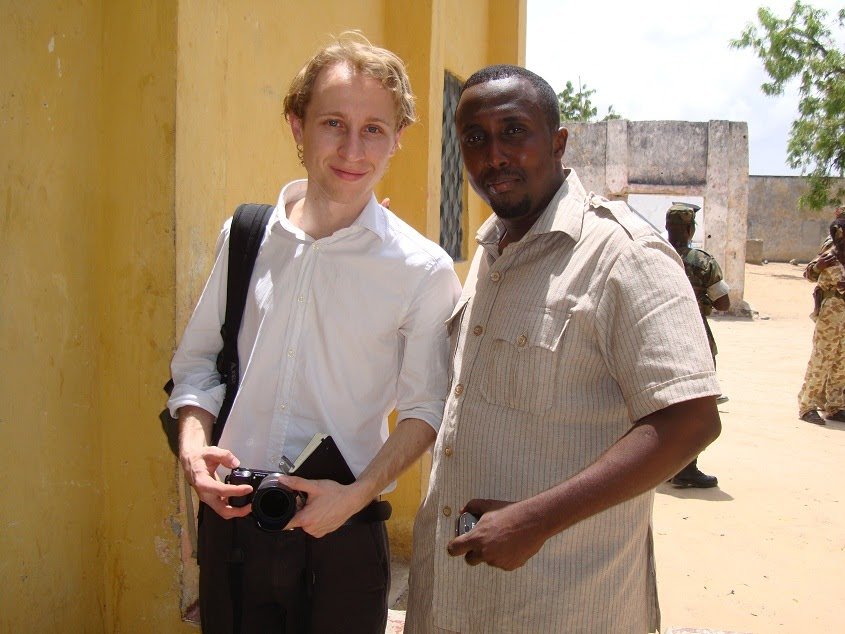

In August 2011, the militant group al-Shabaab withdrew from Mogadishu, Somalia. After 21 years of war, the city was devastated. In November I was contacted by the city government, who sought my assistance in reconstructing the city. There was very little money and much work to do. At the time I was living and working in Afghanistan, but knew that Mogadishu must quickly seize the opportunity.

When I began working in Mogadishu there was no international presence and no resources. As the Mayor, Mohummud Nur, said "we have no money, no partners, no help - we have 21 years of war and the UN, and the UN has been here the entire time." When he asked what I could provide to change that, I offered little than a desire to better understand the problem. I boarded a plane and several more to follow.

Traditional methods in urban planning were impossible. After several months of street-level research in Mogadishu, I developed and array of interventions to maximize the sparse yet accessible resources in hope of creating a magnet for greater resources acquisition.

Furthermore, commuting between Mogadishu and Kabul for several years, I found that the majority of urban planning beliefs and processes are outdated and ill-fit for today's conflict cities. Much of my emergent philosophy concerning alternative approaches to urban planning has been captured in my blog, Humanitarian Space.