Refugee Camp Design and Development

Dadaab Refugee Camps

The Dadaab Refugee Camps make up the world's largest refugee camp complex, hosting nearly 400,000 refugees within an area originally designed to hold 20,000 people. The complex was founded in 1991 and continues to grow each day. I spent 90 days in Dadaab in 2008 and also did follow up research in 2010. At the core, my primary question was simply "how to design a better refugee camp?" yet the complexity the problem demands an incremental approach to this problem and from multiple points of view.

Above: Drawing as Notation and Sense-making Below: Extensive ethnographic research practices including cognitive mapping

Research Methods

Initial research relied upon qualitative interview techniques, focus groups, and quantitative surveys. All interviews were conducted in the immediate context of the problem discussed. Non-participant observation continued to inform my understanding of the problems underlying effective shelter solutions that are conducive to the informal economy and social practices.

Seeking a more tactile means to understand the problem, interviewed refugees also drew maps of their homes. No direction was given in the mapping exercise, and images varied widely. This process uncovered uses and concerns not otherwise addressed by humanitarian aid organizations, such as concerns for livestock, prayer, and childhood education.

Many of these findings, when presented to the NGO, were met with great surprise as the issue of shelter had been engaged as an entirely technical problem.

Insight

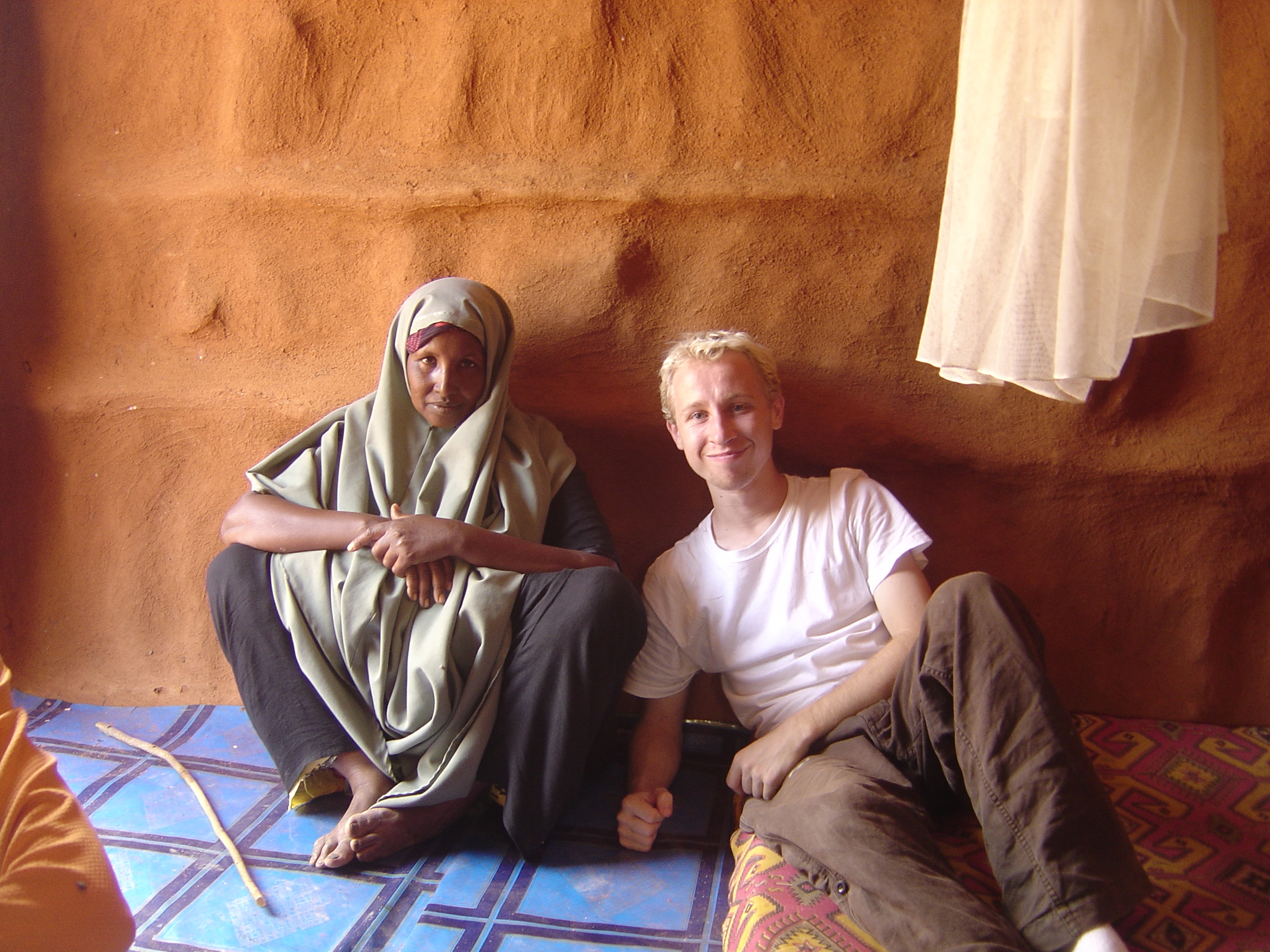

To go deeper into the social-materiality of the problem, I asked many people in the camps if I can participate in the construction of informal housing. In this manner it was possible to acquire direct engagement with the tacit knowledge of housing construction among the diverse cultural groups living in the camps. The laborious process further informed a stronger relationship with the community, expanding my reach, and provided a means to uncover new paths of information. Eventually the tactile and practical integration of the informal economy, cultural norms, social systems of organization, identity construction, and material assemblage became visible within the housing design and consolidation process.

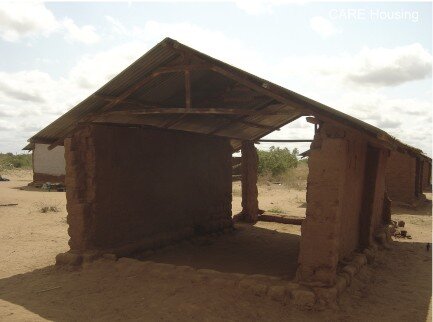

Transitional shelter co-design output using local knowledge and assets. 2007

Project Output

Though far from perfect in its first iteration, the diversity of research methods led to the design of a transitional shelter that met the immediate objectives, more importantly, could provide access to long term goals.

Sense making exercise concerning the laws and the inputs and outputs of Migration/Development/Shelter/Security

Lessons Learned for New Futures

In consequence of the early Design Research conducted in the Dadaab Camps, all work since has consisted of iterative phases of social immersion, stakeholder engagement, and material practice. As determined by the availability of time and materials, traditional design methods such as diagramming and rapid prototyping can frequently take place on site.

However, the most important lesson learned - hard learned - was that impactful design requires a sophisticated understanding of the dominant legal frameworks when engaging highly complex problems.

Within the terms of international refugee law, and many host nations, this is a perfectly viable alternative to tent cities. Sipus 2010.

Following an additional year of study of international refugee law at the American University of Cairo, Egypt, Centre for Migration and Refugee Studies, it became vividly clear to me that the greatest restriction to the design of better infrastructure and facilities within displacement camps is the body of systematic beliefs held by humanitarians, engineers, architects, and designers about what a refugee camp, or other such entity, should be. Ultimately, there is little reason - if any - to justify the proliferation of dusty tent covered deserts. Within the boundaries of law, it is perfectly feasible to introduce other actors and processes into displacement camps. Case in point, while Ikea continues to fabricate shelters and goods for refugees - they could just as well open a store and supply the same goods they sell everyone else in the world. There is no reason that individuals in need of refugee status also must have substandard goods. Why does Ikea hesitate? It likely has more to do with their idea of the refugee camp than any legal, logistical, or design necessity.